Tuesday, September 22, 2009

Calender of Sound - Hermeto Pascoal

I tried to tuck his name away into the back of mind, but I forgot it and I've only recently rediscovered his body of work for myself. So I've been listening to Só Não and looking for info on the man and his catalog. I was astonished to learn that everyday from June 24, 1996 to June 23, 1997, Pascoal wrote a new composition, including an extra one for the leap-day. Yes, that's 366 new works in one year!

Let's set aside the "How did he possibly do this" part of the equation and ask "Why did he do this?" His motive was simple, he wanted to give everyone a unique song for their birthday. This is the crazy, relentless genius of Hermeto Pascoal!

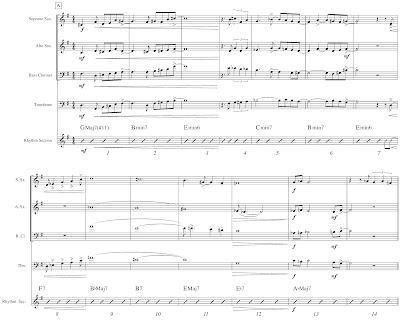

The collection was published in 2000, but is sadly out of print. However, and this is a big however, the entire collection is available for free on his website and the project is called Calendário do Som. It's an incredible resource and an open look into a brilliant composer's music.

A couple of CD's have been recorded that feature selections exclusively from Calendário do Som. One is Itiberê Orquestra Família's Calendário do Som, which is comprised of twenty-seven days from throughout the year (some of these are available via their myspace page). The one I'm currently listening to is Fabiano Araujo's Calendário Do Som - 9 Dias.

The beauty of these compositions is stunning, and I'd highly suggest checking them out. I hope to take apart a few of these tunes and blog about them at some point, but I still have a post on Michael Gibbs forthcoming. In the meantime, enjoy the song of the day.

Saturday, September 5, 2009

Free Scores from Darcy James Argue and Graham Collier's Book on Arranging

I just noticed tonight that he has two of his scores posted for free download: Desolation Sound and Transit. I can't wait to dig into these...

He also seems to get get a lot of good discussions going.

Another thing that I'm excited about is Graham Collier's book, The Jazz Composer: Moving Music Off the Paper. I'm hoping to be able to get this soon. It looks like a much needed text that will delve more into the Ellington/Mingus/Evans school of writing and arranging!

Friday, September 4, 2009

New Tracks Uploaded

A new post on composer/arranger/trombonist Michael Gibbs is in the works and will be up soon!

Wednesday, June 24, 2009

To Each His Own

Tuesday, June 23, 2009

Unconventional Voicings in Gil Evans’s Music – Applying It to My Own Work

Monday, May 18, 2009

Unconventional Voicings in Gil Evans’s Music

Sunday, April 26, 2009

The Purpose Therein

Starting this 'blog is an idea I've had for some time now, but the catalyst has only recently arrived; my thanks to Do The Math for starting the proverbial fire under my ass.

So why add another webpage to a cyber-world already flooded with split-second self-journalism? Well, I suppose that part of it is inevitably going to come down to narcissism, however I'm hopeful that this webpage can provide an arena where 1.) I can share some of my ideas and struggles as a would-be jazz bassist, composer, and arranger and 2.) I can receive feedback from, and dialogue with, a vast community of fellow musicians.

Another reason is my hope that the pressure to regularly post something will help me to continue in a routine of analyzing, transcribing, arranging, and composing music. Consequently, these are the things that I intend to fill this webpage with.

Other music-related ramblings may pop-up, but my goal is keep the 'blog focused primarily on composition and arranging.