As I mentioned in the previous post, I've spent a fair amount of time studying Evans's music. Ripping stuff apart and understanding how it works has always fascinated me. As a kid, and particularly as a teenager, I had to understand how the things I was interested in worked. I started playing the electric bass in eighth-grade, and before long I was pulling the pick guard off, looking at the pickups, and researching guitar maintenance and repair issues. I also started planning to build my own instrument. Even now, if something fascinates me enough I have to get inside of it and understand what makes it work. This is why, for example, I can tell you a lot about how an electric guitar pickup functions through the principle of transduction, but my car's engine remains a mystery to me.

Purely academic knowledge of a subject does not automatically translate to practical application of it. I never built my own electric bass, I think that the cost was too prohibitive for a lad of fifteen, and soon I became obsessed anew with the upright bass. Anyway, my point is that I think that it would be utterly pointless for me to have spent a lot of time analyzing Evan's music without being able to apply it to my own writing. Also, I think that it shows a deeper understanding of a subject when the presenter can show evidence of it affecting his work.

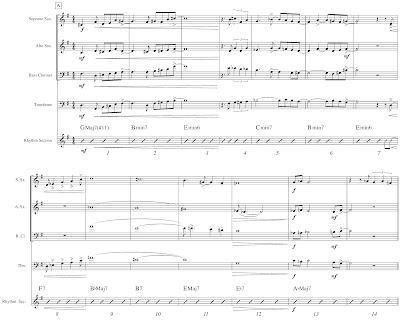

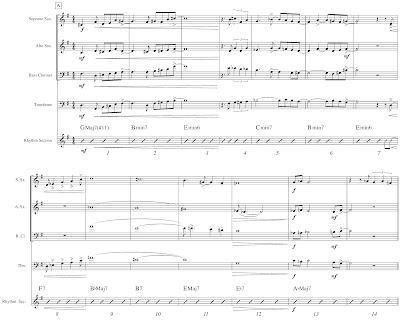

The above example is an original composition of mine called "Yossarian's Crazy." Evans's frequent use of seconds at the top of his voicings was particularly present in my mind as I was writing the arrangement. Consequently, the alto saxophone is commonly placed a major or a minor-second below the melody. At points, these clashes occur in preplanned voicings and were intended to add extra tension to the texture (downbeat of m.1, anticipation of m. 7, and mm. 25-26). However, in other instances they are a result of linear writing (upbeat of beat 3 in m. 1, and beat 4 of m. 6). Linear-writing is another standout trait of Evans, and it's something I'll probably post on at a later time. For now, I'll just point out Bill Dobbins's Jazz Arranging and Composing, A Linear Approach as a good place to begin exploring the linear concept. The example included below is a little snippet of an arrangement of "The Wind Cries Mary" that I've been working on. What's at work here is something I've been realizing about Evans's writing: his use and control of dissonance was absolutely masterful. Don't take this to mean that he used as much dissonance as possible in every situation. Quite to the contrary. Evans sometimes used what our ears (by whom I mean post-Baroque listeners) don't consider dissonant at all. One of the things I do think this means is that Evans realized that dissonance can be added into a voicing through a myriad of ways. Altered chord extensions (#9, b13, etc…) are probably the most common way we approach this in jazz. Evans, however, used several methods in addition to the aforementioned extensions. These included added-tones (yet another potential post for the future), incidental dissonances (often a result of linear-writing), and chord-tone ordering (the subject at hand).

These techniques introduce dissonance in their own ways and impart their own kind of flavor to the moment. What's unique about chord-tone ordering is that it allows the composer/arranger to introduce more tension into a voicing without changing the function or the fundamental character of the voicing. A dominant seventh can be made to sound (more) dissonant just by sticking the root next to the seventh, but no new notes have to be added.

For this passage of "The Wind Cries Mary" I wanted to preserve some of the harmonic simplicity of the original version. Adding a ton of altered extensions or reharmonizing the melody right off the bat just felt I was saying, "Look at my cool jazz chords!" That's certainly not the result in every situation, but I just didn't think it would sound right in this case. So I elected to go with simpler harmony, however I still wanted the voicings to sound a little different. The dissonance of the seconds stands out because these voicings are relatively simple. Also, they're mostly found at the top of the voicings, and this draws even more attention to them, which also necessitates attention to dynamics and blending.